Vinnie Jones

As the star of over 100 films which began with a role as the shotgun-toting enforcer in Guy Ritchie’s 1998 Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and blockbuster follow-up, Snatch – in which he played the cuddly Bullet-Tooth Tony – he has traded lining up alongside Micky Whitlow and David Batty for Brad Pitt and Burt Reynolds. In 1990, he was holed up in the Leeds suburb of Shadwell, but these days resides in Hollywood, where he is almost certainly the only superstar actor with “Leeds United – Division Two Champions 1990” tattooed upon an ankle.

However, even given the good fortune I had when speaking to Gary Speed, securing an interview with a Hollywood actor seems as likely as landing a part in a Guy Ritchie film. Leeds United haven’t been in touch for years. Emails to Los Angeles-based film agents inevitably go unanswered. I’m about to give up when I discover that when he’s not portraying a succession of stern-faced hardmen, he’s spent the last four years also managing an LA-based “soccer” team of actors, ex-pats and porn stars, the Hollywood All Stars. A hopeful email to their website produces a reply within the hour. “Vinnie would love to talk about Leeds United, would you like to do it over the phone or in person?”

Three days and one swiftly-drained bank account later, I’m driving a hire car up Mulholland Drive, the famous long and winding residence of the top stars which gave its name to David Lynch’s 2001 film noir and a David Hockney painting, and seems a long way from Beeston Hill, the long and winding path to Elland Road.

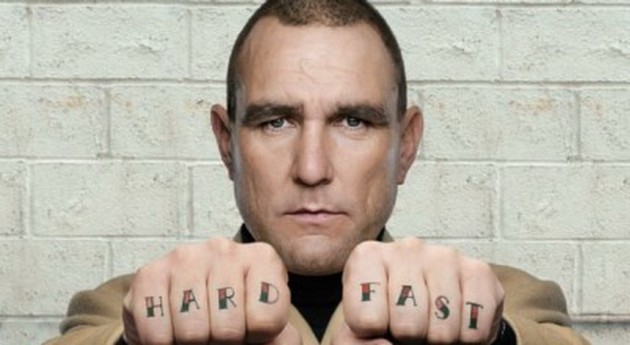

Jones’s house is easy to find because it’s painted in Leeds United white and has a Union Jack outside. I ring the buzzer and suddenly there he is, every bit as stern and menacing as he was in Lock, Stock or the infamous Wimbledon-era photograph of him grabbing Paul Gascoigne by the testicles. Access to the house means walking past a garage containing two Harley Davidsons, a sports car and a gigantic Range Rover, and I’m suddenly in a white open plan kitchen where Jones is surrounded by guitars signed by Slash and Bryan Adams. Two tiny Chihuahuas yap around that tattooed ankle like two miniature David Battys, and there’s a giant poster for the film that changed his life.

“I’d never have thought of anything like it,” admits the midfield-turned-screen enforcer, welcoming his jetlagged guest with a refreshing cuppa. “I was assistant manager at QPR. They liked what I done. Never looked back.”

Until now. In fact, despite being a much bigger – worldwide – star than he was at Leeds, and it being over 20 years ago, it takes about 45 seconds to get Jones talking about his life and times at Leeds, which he still regards as one of the crucial and most enjoyable experiences of his 46 years on the planet.

“It was one of the biggest, best and proudest decisions of my life,” he insists, as we leap into the Range Rover to drive to a Beverley Hills golf course, where the interview takes place in searing heat with Jones driving a golf buggy like he’s in a car chase, with me sunburning by the minute and hanging on for dear life. We join his golf pals with names such as Snowy, Bob The Nob and Mikey, similarly big characters who have no idea that their famous movie pal had a previous “soccer” life at all.

“He’s my best friend, you better give him a good write up,” urges a man with a sliver of a moustache which makes him a ringer for Lee Van Cleef in The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, drily.

“Because if you come to Vegas, son, you might have problems.”

Yikes. But becoming a Hollywood superstar isn’t the first time Vincent Peter Jones underwent an improbable metamorphosis. In 1986, he was a hod carrier turning out for non-league Wealdstone when Wimbledon’s manager Dave “Harry” Bassett took a £10,000 gamble that he could cut it in League football. Wimbledon (the original Plough Lane club, not today’s Milton Keynes-based Frankenstein of a franchise which have been renamed MK Dons) were on an adventure of their own – a whirlwind rise which took them to the First Division just four years after they were in the Fourth and nine after they joined the Football League for the first time since being formed in 1889. In 1988, they’d pulled off one of the biggest FA Cup shocks ever, triumphing 1-0 at Wembley over Liverpool team containing the likes of Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish, who Jones delighted in informing before the game that he would “rip your head off and crap in the hole”.

But the following summer, he was disillusioned, fed up with life on £500 a week and under Bassett’s successor Bobby Gould, with whom he’d had a “pushing match” at Luton. So he told owner Sam Hamman he wanted out.

He says that Hamman tried everything to dissuade him – “You’re the heart of this club, when you don’t play we struggle. He put the tears on. But it was like that for years at Wimbledon, y’ know” – but suspects this was half-hearted, and says he later found out Gould wanted rid of him as well.

“So Sam says – I’ll never forget it – ‘Things will happen a lot quicker than you think.” As the Welshman tells it, two clubs were interested in his services: Aston Villa (managed by future England manager Graham Taylor, who’d been his schoolboy manager at Watford, but released him) and Leeds. He remembers LUFC managing director Bill Fotherby calling him on his phone. “That was the days of the car phone, with the lead an’ all that,” he says, inimitably. “The walkabout ones were like fackin’ breeze blocks.”

Fotherby – as per his reputation – gave him “the full nine yards. Charlie big bananas. He was more like a market trader than a chairman.” But Jones had heard enough. “I’ve ‘ad a few punch ups an’ that but when it comes to money and friendships I’m a very honourable bloke,” he explains, over the roar of the golf buggy. “Fotherby was first on the phone, so Taylor [who’d had him as a schoolboy at Watford, but released him] rings up and I tell him I’ve already spoken to Leeds.”

So you chose Leeds because they phoned first?

“Simple as that,” he insists, stopping the vehicle for a moment. “Weird twist of fate.” And off we roar again.

One of Wilkinson’s bigger early buys at £600,000, he knew he’d made the right choice before he even made the ground, stepping off the train to glimpse a newspaper headline, “Jones in Leeds talks’ and thinking “Wow, this is massive.’” At Elland Road, he was impressed that everyone from general manager Alan Roberts to the tea girls seemed to be pulling in the same direction. When he arrived, another player was due to sign from West Ham, but was dragging his feet. “Alan Roberts was like, ‘If you’re umming and aah-ing about coming to Elland Road you can fack off.’ They were on this massive, positive thing. No jolly up: 110% or nothing. I thought ‘If you cut these fackers in half they’re going to bleed Leeds United.’”

Jones instantly felt likewise, but reveals a funny story – at this point he didn’t know who the manager was. “Fotherby – I love Bill – keeps giving me the spiel, ‘Howard Wilkinson, Howard Wilkinson’,” he says, confessing that he was confused with then-Everton manager Howard Kendall. “I said ‘Howard Wilkinson? He’s at Sheffield Wednesday?’ ‘No, he’s here now!’” he roars. “Cos apparently he tried to sign me when he was at Wednesday. He was a big fan, apparently.”

Jones was desperate to sign, but even then was a good enough actor to keep a poker face during talks, with Fotherby and board member Peter Ridsdale, in the latter’s office at club sponsors Top Man. Agents had started to appear in football, but Jones negotiated himself. He remembers seeing a bottle of champagne on the table – an early glimpse of the largesse Ridsdale notoriously brought to Premiership-era Leeds United as chairman – and thinking “‘I’ve got him. I was on £500 a week and asked for two and a half grand, plus a BMW. With side skirts. He never even twitched. I remember thinking ‘Fack. I could have doubled it.’”

But money was a side issue. Jones had arrived at a club where he knew he could play a major part in something special.

“Alright, Leeds were in the Second Division, but now I could really become someone,” he explains. “This wasn’t Wimbledon, where people tread on you like fackin’ beetles. All of a sudden, when you walk through the jungle, you’re this big fackin’ white leopard! Someone that’s respected.”

“They told me they wanted to stamp out the racism thing,” he continues, unstoppably. “One of the first things I did was sing from the rooftops that racism was nowhere in my vocabulary. My best mate [Wimbledon’s John Fashanu, aka “Fash the Bash”] is one of the biggest fackin’ black players in the League and I’d die for him. So I said ‘This is not white or black or Asian Leeds United, but Leeds United… and we need all of you to make this town fantastic.’

“On the one hand, you had Strachan, who was the gentleman, who’d come from Man United. But Wilko brought the Crazy Gang and the Culture Club together,” he says of the unlikely pairing, paraphrasing John “Motty” Motson’s description of the Liverpool-Wimbledon Cup Final. “Because, as Gordon will tell you, I was a leader of men, and he was the leader on the training ground and off the pitch. I became a better player because of Gordon. I became a better person because of Gordon.”

Jones had arrived at Leeds more infamous than famous, one of the most controversial characters in the game after much criticized challenges on Gary Stevens and Kevin Ratcliffe, and the incident with Gazza, which people now think was a bit of fun.

“It wasn’t a bit of fun,” Jones admits. “The boys had come up to Newcastle and said about this wunderkid that fackin’ tore teams apart. So I ‘ad a job to do an’ Don Howe will tell you to this day that was one of the best man marking jobs he’d seen. It was my job to man mark him out of the ground and I was so fired up I got hold of him,” he deadpans.

However, after a ruckus in a pre-season “friendly” against Anderlecht, during which Noel Blake was sent off, a severe dressing down from Strachan proved crucial to the way Jones performed at Leeds.

“Strach was like ‘What the **** are you doing?’ At Wimbledon it was intimidate them. He was saying that we could intimidate them by playing football. Wimbledon were pressure from the top, snap tackles. At Leeds we had a pattern, pass it to Strachan. Whatever, in that season I forgot about chopping people. He said ‘You’re not here to kill people, you’re here because we know you’re a good player and we know you can pass the ball.’ I thought, ‘He’s right.’ My reputation was there on the team sheet. People didn’t wanna tackle me, so it gave me the space to play.” Thus, he received just two bookings all season after Strachan had told him “We’ve got a lot to do this season and we can’t have this childish bullshit. We’ve got to be this force to be reckoned with”.

“The bond between us… what he [Wilkinson] did was a master thing, but facking cruel by any standards,” he continues, changing tack. “I thought ‘Facking hell, that could be me one day.” His voice falls to a conspiratorial-sounding whisper during the golf shots, as he observes how Leeds had struggled in the Sergeant’s first few months, which led to the establishment of the leper colony”.

“Vince Hillaire, Brendan Ormsby, John Sheridan, Mark Aizlewood an’ all that. Nice fellas,” he chuckles. “But we’d done the running and that and he said ‘Right you lot, over there. Do what you want.’ Basically, keep yourselves fit an’ that, but they were rejects. None of them really did any good. Shez [Sheridan] went to Sheffield Wednesday dinne?”

Jones expands on the incident in his book, the ruckus with Bobby Davison in the player’s lounge.

“Him and Ian Baird,” he recalls, naming what were then the two main strikers at the club. “Bairdy was insecure, couldn’t carry the line, he didn’t know whether he was going to be involved. It was all starting to get a bit them and us, and one of them made this snidey comment like ‘We pass the ball here.’ And I just flew, gave ‘em both a smack. That was that. As I went in I saw fackin’ Strachan leg it up to Wilko’s office. So I’ve got all my gear. I’m going back to Wimbledon.” He remembers how coach Mick Hennigan – a “man’s man”, who he loved – came to see that he was alright.

“Next thing – and this is brilliant captaincy for you – Strach tells me to see Wilko. Mick tells me to calm down. So I’m in Wilko’s office going ‘Fackin’ give it to me, you cant. I’m facking off down the M1, deal with it.’

“And he’s gone ‘I’m disappointed in you. I’ve just been in there, and there’s no blood.’ That’s what he said! I’m like ‘What do you mean?’ And he said ‘Why do you think I brought you to this club? To sort those ****ing wankers out.’”

Prior to this moment, Jones admits that he’d been lonely – running up “ridiculous” bar bills in the Leeds Hilton and even suggesting to Fash The Bash that he may have made a mistake moving north.

“But from that minute I just went ‘Whoooooooosh!” he insists, perfectly mimicking an aeroplane. “That incident changed everything for me. That was the first time Wilko had said anything like that to me. I realized I was a major part of this thing.”

Why did the fans take to you like they did?

“I started two weeks early. I was the fittest I’ve ever been in my life. Then I came down on my ankle and it just went bang. Next thing, I’m in ****ing plaster for pre-season. Anyway, we got smashed at Newcastle [5-2, on the opening day of the season] and I’m sitting on the fackin’ bench. But we had a midweek game against Middlesbrough and the pot came off. Wilko said ‘How are you?” I was chomping at the fackin’ bit. I’ve come roaring on, the crowd has gone facking nuts.”

“I went to fackin’ head the ball and missed it completely,” he chuckles, “but then – and bear in mind I’ve waited eight weeks for this – I picked the ball up and passed it [towards the Boro goal, where the opposition full back chipped it to the keeper]. And I remember it just floated over him,” he says. “That was the end of the game. I’ve run up to the Kop. ‘WAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAH!’ And they took to me right away.” The photograph of Jones up on the old Kop railings – installed to keep the players off the pitch, not vice versa – is among the most iconic of the era, beautiful in its machismo and savagery.

The Cult of Vinnie had begun.

For more fun After sport’s career news click here.

Read news from our Did you know? section, every Friday a new story, tomorrow read about Special alphabet sums up a year of success for SOPOT