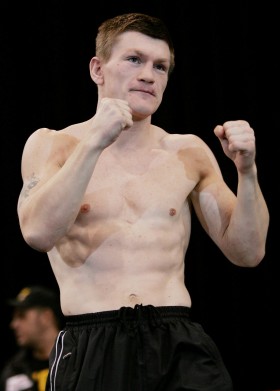

Ricky Hatton

It is said sports stars die twice, the first time at retirement. If you are no longer a sporting superstar, then who are you?

Play media

Someone who knows this struggle better than most is boxing legend Sugar Ray Leonard. He vividly recalls the feeling he experienced at the moment of victory and how he found its allure too enticing to resist.

“Nothing could satisfy me outside the ring,” he says. “There is nothing in life that can compare to becoming a world champion, having your hand raised in that moment of glory, with thousands, millions of people cheering you on.“

Speaking to BBC Sport, Leonard reflected on how his inability to separate the boxer from the man became all-consuming, forcing him to the depths of depression and leading him to make repeated comebacks.

“When I came back I felt safer in the ring. I could defeat those demons that possessed me outside the ring,” he recalls. “It was such a release when I trained for a fight because all of a sudden I’m totally clean, whether it was from cocaine, or alcohol, or depression. It gave me a sense of calm.“

Two of Britain’s best-loved sportsmen, boxer Ricky Hatton and former England cricketer Andrew Flintoff, have suffered from depression. Both recently made high-profile returns to professional sport, each citing unfinished business as the main motivating factor.

For athletes who are at – or close to – their physical peak, whose lives have been dedicated to intense physical challenge, retirement can lead to a range of mental and physical problems.

Some people are sceptical as to how sports stars, with all their wealth and fame, can suffer from depression, but sports psychologist Andrea Firth-Clark, from the University of Greenwich, argues “they should not be denied the same level of understanding and help that anyone else may expect“.

Sense of loss

Bill Cole, a world-renowned peak performance coach based in California, has worked across dozens of different sports and seen many athletes struggle to come to terms with their retirement.

A significant contributory factor is the profound sense of loss they experience.

“Athletes identify themselves by what they do,” he says. “Take that away and they feel abandoned and naked and at a loss for how to make sense of it. It’s as if a major piece of themselves has gone missing.“

Leonard agrees. He claims that this feeling is common among top-level athletes.

“I spoke to my friend Wayne Gretzky [the legendary ice hockey player] recently about how you have that feeling of loss if you’re not a boxer, not a hockey player,” said the 56-year-old American. “Sometimes we don’t listen to our bodies. The body says it’s time, but within our hearts and minds we tell ourselves ‘one more time’. It’s always one more time!“

Biological factors

In Bill Cole‘s experience biological factors can also play a significant role in an athlete’s struggle with retirement.

“Athletes had regular doses of serotonin daily for many years, and suddenly, that has decreased or stopped outright. That is a huge upset to the chemistry of the body,” he says. “Even some retired athletes who continue to exercise fail to get the endorphin highs since they no longer compete.“

Tunnel vision

Leading sportsmen and women have lived a regimented training routine for years, often since childhood.

Cole says an athlete’s “tunnel vision and regimented life” is part of the reason why top-level sportsmen and women struggle more with retirement than those in other walks of life.

“This compartmentalised existence, as much as it served them in their rise and sustenance as a prolific athlete, can feel stifling, yet secure, and to give it up suddenly can have an athlete feeling quite lost,” he stated.

Britain’s double Olympic rowing champion James Cracknell feels this focus is significant.

“I think people suffer from depression after retiring from sport because they aren’t sure where to apply that focus,” he said. “There is a lot of focus and a lot of selfishness in sportsmen.“

Cracknell believes retirement brings a void where the comfort of a training routine once was.

“If they’re honest many sports stars haven’t grown up that much,” he continued. “You’re institutionalised in that you’re told when to be at training and what to eat, etc. I think that hand-holding routine can lead people to feeling lost when they retire, so they need to find something to replace it.“

Cracknell spent the years following his retirement from rowing taking part in a series of endurance events to try to satisfy his competitive nature. It was during one of these events that his life was to change dramatically.

While attempting to cycle, row, run and swim from Los Angeles to New York within 16 days, he was knocked off his bike by a petrol tanker in Arizona, causing severe frontal lobe damage to his brain. Cracknell and his wife Beverly have written a book together, ‘Touching Distance’, poignantly describing the trauma of his recovery.

“As a sportsman, competing can seem the most important thing to you,” he said. “Since my accident I have a different scale of importance. Being the best father I can be to my kids has moved to a level of importance that I probably didn’t quite view it before, because I hadn’t been 24 hours away from never seeing them again.“

The grieving process

The factors behind an athlete’s retirement can be crucial. Firth-Clark believes the fact that many are forced to end their careers for negative reasons, such as injury, diminution of ability and de-selection, adds to this feeling of loss.

“This negativity leads the athlete to go through what is called the grief process – denial, isolation, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance,” she pointed out. “The focus is on the loss of a way of life and not on the beginning of a new one.“

Ricky Hatton initially retired in the aftermath of a brutal knockout against Filipino Manny Pacquiao in Las Vegas in May 2009.

This defeat led the then 30-year-old to retire and descend into a spiral of well-documented problems which left him contemplating suicide. When he made a return to the ring in November 2012 he said his overwhelming desire was for redemption, both for the manner of his defeat by Pacquiao and the subsequent problems he endured in retirement. His comeback, however, ended in defeat.

Acceptance

Sports psychologist Dr Victor Thompson recognises the challenges of retirement: “Elite athletes such as Premier League footballers relish testing themselves by competing in front of thousands of people, either willing them to succeed or fail. This is the type of challenge and buzz that you don’t generally get in everyday life.“

Having plans in place for their retirement, along with having a strong support group around them, are important components for helping athletes make the transition.

The last word goes to Leonard, who adheres to the maxim that in acceptance comes peace. “I think I’ve made more comebacks than anyone in any sport,” he said. “If you don’t accept that nothing else will give you that kind of glory or satisfaction, you’ll continue to search and search.“

He concludes with some advice for retiring athletes: to surrender to the fact they’ve had a great run but now need to pursue something else. While it may not quite bring the same buzz, it can satisfy that urge and lead to contentment.

“That’s when you’re complete and that’s when I became satisfied with what I’d accomplished. I knew I’d had my day in the sun,” he concluded.

For more news from this section click on After sports career.

Read news from our Did you know? section, every Friday a new story. Tomorrow read about Ten fun facts about Volleyball